|

|||||

|

|

|||||

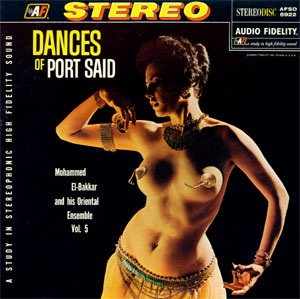

| Port Said ......portal to the Isthmus of Suez......exotic jewel atop the shield-shaped Sinai Peninsula ...... . city of commerce by day and romantic adventure by night...... . starting point of desert caravans and terminus for lost souls ...... burial ground for princes, soldiers, sailors, beggars and thieves......crucible for love and hate, greed and cruelty......melting pot of the Middle East.

By day you can smell the port's pungency, which has hung over the city like a pall for centuries. If you idle in the streets fronting on the harbor, you can see the busy entrance to the canal, where tankers line up waiting their turn to weigh anchor for the rich oilfields to the south. Fishing boats dot the quay, bobbing like corks until the next time they put out for the blue Mediterranean, and the too exude their own peculiar smell. Occasionally you can see dragomen scurrying towards the docks clad in long robes and hauling their boxes of Turkish delight. There are also gulli-gulli men toting chickens, coolies clad in filthy rags and laden down with sacks of coal they are carrying to the bunkers of freighters, old men with sacks of roasted nuts perched on their heads, merchants and clerks, sheiks rubbing elbows with peddlers. At night the port is transformed, becoming one of the most dangerous, rawest places on earth. Tall towers and high balconied buildings inspire a sense of foreboding. You have the impression that anything can happen, and it generally does. The city pulsates with an enticing rhythm. You sense it in the swaying of the tassels on the natives' tarbooshes ant the undulations of the belly dancers. Young sailors swagger through the streets, concealing their misgivings with false looks of bravado. Hidden away in the shambles of back streets, in tottering tenements and well-upholstered bistros, purveyors of sin are holding forth, In some of them, naked girls plastered with lipstick prepare their acts for the salles des exhibitions. Perhaps some urchin will accost you as you pass by, making a pass at your watch or wallet; or some villainous creature will hurl a stone at you from an alleyway. But more likely it will be the brothel keepers beckoning from their doorways, screeching peddlers or shouting hack drivers, all of whom add to the tempo of life. Music, too, pulsates through the night in Port Said. As you hear the strains of some oriental ensemble, a chorus of strident voices echoing through the sultry darkness, or the wail of a solo pipe, you understand the meaning of the saying that the city feeds on the flesh of strangers. Somehow you are always a stranger in the port, no matter how long you've been there. This is because one's identity as an individual becomes obscured by the throngs of people who fill the streets throughout most of the day and night. In Port Said you are drawn inevitably to the Djeama'a el-Fna, a large, noisy, crowded place about the size of a square city block. The natives say that the Djema'a el-Fin, is never empty, and if you come upon one at any time except during the hours of early morning, you're bound to conclude that it could not be more crowded. It has a fascination quite unlike anything, the Djema'a el-Fna, seething with humanity. Waves of djellaba hoods moving closely together give it constant motion. Even faces appear to be all alike as they merge into the general turbulence. Occasionally the aimless movement of the crowd's current is broken by the antics of a cancer, by tumblers, sword swallowers or men spinning matchlocks. Captured by the murmur of the crowd and the wail of music, you stop at one of the cafes that border on the square. You seek out the terrace to get away from the mob. Naturally, you can't just sit by and buy nothing. So you order a drink or coffee, which cost twice what they would at a place of the street level. But then, there is the view, towers and domes stretching as far as the eye can see. Your eyes return to the crowd, always different, always a myraid of color even in the shadows of night, and to the dancers, the tumblers and sword swallower. When you're not riveted to the Djema'a el-Fna, you're apt to make your way to a bazaar. These are rambling and mysterious, brightened during the day by shafts of sunlight coming through the roof and made more alluring at night by candlelight. The bazaars are full of stands displaying fabrics of every sort, jewelry, handmade metalcraft, carpets and vegetables. Turbaned figures constantly wander through the aisles, doing their share of pushing, shouting and bargaining. One stall is likely to feature a band of native singers, telling in strident fashion age-old stories of love and adventure. Another will reveal belly dancers going through the choreographic ritual of the harem, and enlivening their performance with meaningful looks and shimmering veils. Still another will hold a dozen of so acrobats stripped to the waist and exercising with dumbells and poles. In the bazaars also you can feel the pulse of Port Said--its antiquity, its atmosphere of cunning, the erratic temper of the natives. If you catch the eye of an Arab, it's difficult to know whether his suspicious glance is caused by distrust, hatred, jealousy or sly humor. Behind his protective djellaba is unmistakable concentration, calculating, deep and often too dark to fathom. The music in this frcording is typical of the Middle East. Much of it brings to mind the ancient slave market, where girls were sold for harems to the accompaniment of sensuous dances and serpentine-like melodies. Instruments used include flutes, drums, bells, cymbals, castanets, clarinets, oboes and strings, as well as many kinds of native percussion sticks or boxes. Even though the listener may not understand the meaning of the words, the piquancy of the music and the inflection of the singers' voices are such as to have considerable appeal. |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|