|

|||||

|

|

|||||

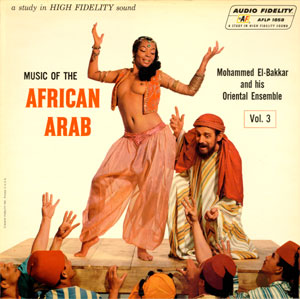

| Visions of voluptuous dancing girls whose lithe bodies twist and turn like writhing serpents about to strike. ...Gruff, unshaven men hungry for the touch of a woman after lonely weeks spent in the desert under a maddening sun. ...Secluded harems where the air is heavy with the aromas of perfume and incense and where luscious fruits are constant reminders of fertility...exotic, crowded market places where lustful men stalk women swathed in Djellaba (head covering) and veils, their dark, flashing eyes a constant enticement to violate the mystery of the forbidden. ...High, arched gateways framing bullet-pocked courtyards where beautiful virgins were once sold into slavery. ...Sailors who find the charms of the girls more attractive that the wares of bazaars. ...Bearded sheiks who count scores of wives as so much property, along with their fabulous jewels, the palaces, oil stocks and other possessions...land where the passion and ecstasy of love is woven into the culture of the people...realm where violence still lurks in the reflection of daggers, the steel of slung rifles and cartridge belts.

These are visions of Arabian Africa. And no one today is able to capture these visions through sound with as much authenticity and excitement as Mohammed El-Bakkar, leading tenor of the Orient and an outstanding conductor and interpreter of Middle Eastern music, Bakkar is on intimate terms with the practice, theory and intrigue of Islamic music. In this recording , as conductor and interpreter he succeeds in capturing the haunting flavor of Arabian vocal and instrumental music, particularly the special earthy quality to which all Arabs give expression. Arabian music in its proper sense is the music of Bedouins in the desert and oases, of urban dwellers in the market places and other public areas, of entertainers in the cafes, the palaces, harems and theaters. Actually, the musical style known popularly as Arabian comprises much more than the music of Arabia proper, and even of nations whose people speak Arabic. It encompasses Morocco, West Africa, Algiers, the African borderland of the Mediterranean through Syria, Iraq, Turkey, Persia and even the northern part of India. It is highly emotional music, limited in range and very free rhythmically. It generally starts with a low pitch, curves upward and returns, repeating this pattern again and again. The rising and falling pitch is typical of both vocal and instrumental music. Arabian music has an overall pattern of melody based freely on one of the modal scales and characterized by stereotyped turns, by a general mood and by pitch (low, middle or high), in which respect it is reminiscent of the Greek classifications of melodies. This pattern is known to orientals as Maqam, originally the name of the stage on which singers performed before the caliph. It is the exact counterpart of a similar pattern known in India as Raga. The most important thing about Islamic music is that it has not only a philosophical basis, but physiological elements as well. These represent actual physical sensations. Hearing the selections in this recording, one realizes that the pervading, persistent melodies evoke something of the mood of ecstasy and trance in the listener which prevails at gatherings of dervishes, ceremonial affairs, ritual dance performances and other festive occasions of modern Islam that have roots going back 2,000 years or more. Islamic rhythm stems from the meters of poetry, and rhythmic patterns appear in all melodies, both vocal and instrumental, and especially in drum parts, which are almost as obligatory in Islamic music as they are in Indian music. Accents are generally given in timbre, rather than in force. Thus, drummers know things like muffled beats, called dum, and clear beats, known as tak; less muffled beats, called dim, and less clear beats, of tik. The clear timbre is usually reserved for the basic rhythmic pattern, while the muffled timbre is used for the muffled beats that mark the sections between the louder beats. Polyphony is not as essential in Islamic as it is in western music. It does exist, however, in three forms--heterophony, drones and occasional consonances. The first is illustrated by what the western world generally calls an ensemble, that is, flutes, zithers, lutes, drums and sometimes strings; also, one or more singers. Drones are used in what is knows as the taqsim, an improvised prelude of solo instruments that often precedes the formal beginning of a composition. Consonances are mainly ornaments in which two consonant notes mingle on the same beat. These usually are large intervals like the octave or fourth. The foregoing is by way of explaining some of the basic structure that shapes the music in this recording. But here all formality and pedantry ends. For the selections represented here are the expressions of the Islamic adventurer, who expects life to have all the variety and flavor of A Thousand and One Nights. Here is music to titillate the emotions of those who love dangerous living (as all Arabs do), of people who consider fear of death a monstrous absurdity (as most Arabs do), of bold souls who believe in living life fully without concern over the future. The Arab does not put money in the bank when he gets hold of any, but rather in a place where he can easily get it and feel it when he feels like doing so. He is fiercely independent, believing that aid comes only from Allah, He believes in letting fate take its course without worrying about where it will lead him, except when it comes to women. For his is a man's world more completely than anywhere else on earth, and he is forever critical and intolerant of women. Listening to the music here, one is reminded that the Arab is a man inextricably bound up in the pattern of civilization into which he was born. This cannot be described in so vulgar a fashion as "hoochie-koochie" music (as so many Americans are apt to describe Middle Eastern music which they hear in movies), only because movies and other mass media of entertainment for most people have associated sin with the "hoochie-koochie" concept. The Arab does not look upon evil and good the way people of the western world do. Here in this recording is a realistic musical portrait of Islamic expression. It is not by any means complete, nor is it intended to be. But in these selections are mirrored through music visions of veiled women, the passion of love translated into musical expression, the humorous interplay of the two sexes, and many subtleties of Arabian life and custom. All are part of the incredible Arabian world.

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|